A fascinating variety of roads, trucks, drivers and their gripping narratives from all walks of lives are encountered by Dhiyanesh Ravichandran on a 15-day, 2,736-kilometre circuit drive in a truck from Delhi to the Himalayas. In this epilogue piece on JK Tyre ‘Happiness Truck’ campaign by MOTORINDIA, supported by Lumax as lighting partner, he recounts the sheerness of diversity in terms of topographical expanse and trucking cultures, while coming to terms with the everyday struggles of truck drivers on roads and a self-realisation that they deserve much more respect for what they do

“Travel isn’t always pretty. It isn’t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts. It even breaks your heart. But that’s okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart, and your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind.”

So said famed travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain, who nailed it down rightly in stating why every trip is life-defining. The time when we at MOTORINDIA sat down to contrive what would later take shape as the ‘Happiness Truck’ campaign, little did we know that we would accomplish much more than what we had intended, to the extent that all the surprises, revelations, wisdom and grasp of the reality we picked up on the way has bettered our perspectives on trucking.

In fact, the experiences gained will even shape how we write about trucks and truckers in the future. Well, the bucket list of the HT campaign included taking a truck to the formidable Himalayas, encouraged by the fact that hundreds of truckers get there every year, via quick detours to all major trucking towns on the way and then engage the stakeholders for happiness and awareness as well as help better their lives and the industry. We did deliver on all those fronts, but what we took back with us – professional learnings and personal experiences, together with a sense of satisfaction – seems way more praiseworthy and noble than what we left behind!

Frankly speaking, the task entrusted on me to recapitulate everything that we took back with us from this trucking trip and condense them all in this finale story is rather delicate and difficult. It’s like asking a symphony orchestra house to compose a brusque 10-second ringtone! With the experience and acumen I have gained from this 15-day road trip, I can go on and on. Maybe I could even author an expansive book on the HT drive! Anyway, let me try my level best to take you to all the memorable moments and high spots of contemplation that this trip engulfed us with.

Of all that enthralled us in this cathartic drive, the sweeping degree of diversity in anything and everything we could see and hear was simply exhilarating. This included the differing topological landscapes, the roads we drove through, a plethora of weather conditions and vehicle traffic associated with it as well as all those folks we met on the way and their lives as assorted as nature. Not to forget the endless medley of foods, dresses, folklores, human settlements, languages and cultures and the unadulterated pastiche of diversity we came across – all this simply held us spellbound.

Road to diversity

We drove up north from Delhi, and the first 250-odd kilometres on NH 44 were a three-lane highway for the most part, which was also the case during the latter part of our circuit from Jammu to Delhi via Pathankot, Jalandhar and Ludhiana. Once past Kiratpur Sahib, the highway gets narrower and twirls around. The ribbon of roads up until Manali was full of tourists’ traffic, made worse by road extension works that were underway. The adventure began from Manali when we started off early towards Leh. That’s when the heavens opened up. It began pouring heavily with a dense morning fog reducing visibility almost to zero. Luckily, our truck was equipped with LED headlamps powered by Lumax, which were of great help in finding our way amid the fog. The LED DRLs, on the other hand, offered the truck a phenomenal road presence even during the day.

The 490-kilometre long Manali-Leh highway (the term ‘highway’ may fool you – remember that most of the stretches are just one-and-half lane wide!) is one-of-its-kind. It is open for only four-and-a-half months a year, with an average elevation of 4,000 metres above the sea level. With our previous experiences, we knew this was going to be the most challenging segment of the HT drive. However, we were ready for it and planned to cross the stretch in three days, with scheduled night stops at Keylong and Sarchu. Incessant rain and traffic prolonged our timely climb to Marhi and Rohtang Pass, which provides the tourists the first view of snowfall or rather ‘ice’!

Beyond this point, the traffic is limited to adventure tourists on their motorbikes and four-wheel drive SUVs, a few truckers and convoys of defence vehicles. The next 20 kilometres from Rohtang to Gramphu is a steady descent. Crossing over, the Lahaul Valley is flooded with sunshine and offers the last tinge of green on the entire stretch, as the greenery disappears with the leeward slope, and all we would encounter for the next 400+ kilometres was just a stark brown landscape and arid earth. Right before the illustrious Tandi Bridge, where the rivers Chandra and Bhaga meet, is the last fuel station before Leh, which is another 365 kilometres away. For the next two days, we had a roster of heights and passes to cross, starting from a steep climb to Baralacha La and the famed ‘nullah’, which has to be crossed before noon as water flow increases thereafter on account of the sun doing the damage, to Tanglang La past Sarchu and Pang villages.

We came across Morey Plains, a stunning open landscape of flatlands situated at over 14,000 feet above the mean sea level. A straight stretch of about 40 kilometres of highway on this plain is flanked on either side by beautiful mountains at some distance. The road seemed freshly laid out, making the cruise the most elegant and satisfying one in the entire circuit. We later crossed the river Indus to pass through Upshi and Karu towns to reach Leh. After two days of activities and photography sessions at Leh, we tanked up the truck and escort vehicles at Indian Oil Corporation’s Lotus Xangpo Memorial filling station at Leh, which is the world’s highest petrol pump at 11,500 feet.

Further on, the Leh-Srinagar NH 1 was neat with absolutely clear visibility up until Zojilla, after crossing Kargil and Drass. It offers a desolate landscape with broken roads, deep drops over the edges, and loose earth on the sides that are vulnerable to frequent landslides. Some 50 kilometres later, the verdant hills of Kashmir brought much respite to our sore eyes and the river Sindh bubbling its way from Sonmarg was so enticing. That was the just the beginning of the opulent Kashmir Valley. We set off from the valley early at 5 am via the ill-famed Srinagar-Jammu highway, where a certain batch of vehicles was escorted by defence forces for the most part of the stretch. Driving through the 9.28 kilometre long Chenani-Nashri tunnel – the longest road tunnel in India – at an altitude of 1,200 metres was a mind-blowing experience, while the peppy river Tawi on the side of the highway reminded us that Jammu town was just around the corner.

Trucking cultures

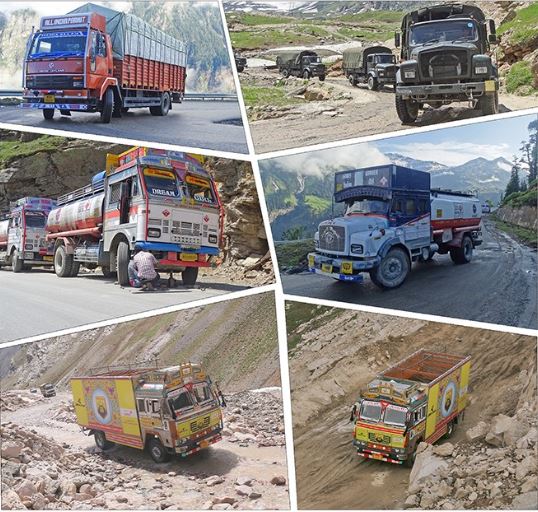

We drove on multiple lane expressways, old-school State highways, countryside roads, mountainous bends, broken or no roads with just mountain trails and ruts. That, overall, turned out to be quite a feat and a phenomenal tryst with diversity. Not just diverse geographical and driving landscapes, we were exposed to a potpourri of trucks and trucking cultures. For instance, once we started climbing the foothills of Himalayas, tractor-trailers and multi-axle trucks with factory-made cabs disappear and rigid-axle haulers dominate the roads instead. Beyond Manali, the only trucks that ply on the Leh highway are 16-tonners with custom cabs, especially Tata LPT 1615 or 1618 and Ashok Leyland 1616.

Also, we could spot a large number of fuel tankers built on Tata SE 1613 chassis with conventional front-bonnet cab design plying on this stretch. Even today, truckers prefer this model for its shorter turning radius and better manoeuvrability on narrow and hilly roads. Border Roads Organisation (BRO), the government agency entrusted with the maintenance of the highway, also has a fleet of tippers – essentially Tata SK series – stationed at various places with a crew of construction workers, who are quickly dispatched to points of emergency involving road damage occurring on account of landslides and other factors.

An armada of four-wheel utility trucks belonging to various defence forces majestically command the entire arc of roads between Manali-Leh-Srinagar-Jammu-Pathankot. They are necessarily Tata LPTA 715 or AL Stallion troop carriers and recovery vehicles, manufactured at Vehicle Factory, Jabalpur (VFJ) under licenses. At Leh, the local road logistics is solely managed by pickup trucks and ICVs, Mahindra Bolero pickup and SML Isuzu trucks. The Kashmir Valley exhibited its uniqueness with an intimidating display of customised Tata SK series tippers with jacked-up ride height and high bumpers. On our way to Jammu, the town of Udhampur on the NH 44 brought back the sight of trailers on highways.

Buses were hardly found on the Manali-Leh stretch, except for those narrow wheelbase, short overhang buses operated by HRTC and HPTDC. However, one cannot escape the aggressive fanfare of Volvo buses en-route to Manali from Chandigarh and Delhi. That’s perhaps the case again on the Jammu-Delhi highway. The Kashmir Valley, here again, grabbed our attention with its flamboyant old buses with ornate decorations both inside and out. They are age-old Tata chassis – standard floor and those built on the 407 platform – and their visual opulence cannot match any of the other buses in the country. The crossing of the river Ravi marked our entry into the state of Punjab, where at the town of Madhopur we met a pride of Bajaj Tempo Hanseat – three-wheeled multi-utility passenger vehicle – that are still in commercial use.

That’s not all. The trucks plying in the regions of Punjab, Himachal and Jammu and Kashmir are themselves ‘cultural artefacts’. They boast a kaleidoscope of colours, art, decorative gears, slogans, verses, and symbols reflecting the taste of the owner’s soil – these rolling canvases are visual delights on roads that one can hardly miss. For truckers, it’s like a rite of passage when they purchase a new chassis. It’s a mode of their artistic and ideological expression. Painted images of Taj Mahal to a village belle carrying a water pot, and verses like ‘Maa ka Ashirwad’ to ‘Stop killing innocent Kashmiris’, the truck arts we came across make for a vivid expression of diverse people and their cultures in this region.

Moving on to the driving experiences I acquired in the HT tour, I must confess at the outset that I may not have even driven a minuscule share of distance clocked by our truck. Despite being familiar with the route and previous driving experience, piloting a truck was still nerve-racking, thanks to narrow and treacherous roads that are broken and slushy, with steep edges on the sides. At several instances, with oncoming truck traffic, I had to go to the very edge of the path to wade through, made all the more risky since the soil cover would be very loose and slushy and a truck could slide away down the drop. It was also a sight to see our helper Bitoo Bhaiya becoming extremely flustered and alarmed at times when the margins on the sides became too narrow. It was also a chore to deal with impatient adventurers on their bikes and SUVs that were more nimble than mine.

A little respect

That’s when I gave up driving and handed over the steering to Vicky Bhaiya, our official driver on this campaign. He hails from Himachal Pradesh, drives all the available four to five months on this very route, and it is his very own truck! He was indeed the right person to pilot the Happiness Truck. Moreover, he seemed intensely and emotionally attached to his vehicle and his job as a trucker. Driving is not just a job for these truckers or a passion statement as it is for me, but more a way of life. Their contribution to our economy is often underrated, while their lifestyle and life chances are emphatically overrated in our society. More often than not, their personal sufferings on the road are untold.

For instance, truckers being made to halt abruptly on highways in Jammu and Kashmir at times have hit headlines, but we don’t get to know how they deal with such harassment in and out on a regular basis. Our team had a harrowing experience when the Happiness Truck got stranded midway at some location on the Srinagar-Jammu highway, as all heavy vehicles were asked to stop on the sides of the serpentine road by security forces. This notorious stretch is known for frequent and long closure, at times due to bad weather or landslides and more often due to restrictions imposed in the name of security. Truckers, but naturally, are the worst hit. They are faced with the loss of time, money, personal dignity, and sometimes the merchandise they haul.

Forget about resting or toilet facilities, they even get stranded at unknown locations for days and weeks without basic food and water! Irrespective of the State we were in, our truck faced countless encounters with police harassment, despite having all valid papers and our press identity cards! Somewhere around Gramphu on the Manali-Leh highway, I bumped into a driver whose truck had broken down two days ago. A fellow trucker was giving him company since they both worked for the same employer, and the required spares were on the way. It gets really tough for these guys when some technical faults arise in their vehicles. More often than not, all drivers have some basic skills to carry out repairs on their own, but still, crawling under the truck to dismantle and repair a radiator or a steering pump at freezing temperatures is no pleasure.

All too often, truck drivers are stigmatised in our society and negatively branded as rash drivers and highway killers, incorrigible drunkards and hooligans, good-for-nothings, and whatever else. They get negative media coverage along with their trucks as noisy monsters that belch out fumes and pollute our cities and environment. No doubt, trucks are harming the pristine environment of the Ladakh cold desert, just as every other vehicle and tourists. But, do we have any practical alternative? All essential goods have to be transported every day, including fuel supplies, with most of it going to feed the defence ecosystem in the region, especially to Ladakh. Suffice it to say that the entire economy would come to a grinding halt if not for trucks and its drivers. Governments and civil society must keep this in mind.

Drivers deserve to be given more credit and respect for their contributions, and not as secondary citizens doing unsanctioned activities. It isn’t easy to be on the road; their working conditions are terrible and salaries invariably meagre. The issues of driver shortage and lack of skilled people in this profession have almost become a cliché in recent times, but that doesn’t mean it is taken up as a burning problem. There are fancy claims that both government and industry stakeholders are taking various steps to address them, but the situation is not improving on the ground. It’s a scandal, nothing less. On the contrary, the informal economy that supports these unorganised truckers and drivers is facing extinction without any betterment or rehabilitation. It’s high time that we get in touch with reality and lend our genuine support to the trucking community, not necessarily for their welfare, but for our good at the least. Do remember, they are the ones who bolster our ‘happiness’ quotient!

Words: Dhiyanesh Ravichandran

Campaign Planning: Avijit Lahiri

Photography: Rajeev Bhendwal