A typical electric vehicle requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant. This underlines the importance of critical metals such as the rare earth elements, a segment in which China holds an almost monopolistic position, opines P. V. Balasubramaniam, Former Director and CEO, York Transport Equipment (Asia) Pte. Ltd., Singapore

Technological developments in the last decade have revolutionised automotive, renewable energy, storage batteries and telecommunication sectors. Future growth of world economy would substantially be led by electric vehicles (EVs), solar and windmill energy, storage bank of batteries feeding grids and communities, telecommunication using fibre optics and satellites. These new applications would demand a large quantity of critical metals that are in the control of a few countries. Challenges about Lithium, Cobalt, Nickel, and Graphite are well-known, but the supply of rare earth elements (REEs) poses a serious threat. REEs are a group of 17 elements starting with Lanthanum in the periodic table of elements and include Scandium and Yttrium with atomic numbers 57 to 71.

There is no substitute to REEs in EVs, windmill turbines, storage batteries, mobile phones, consumer and industrial electronics, fibre optics, aerospace, defence and space. International Energy Agency (IEA) in its report in May 2021 titled ‘The Role of Critical Metals on Energy Transition’ points out that clean energy technologies such as EVs, solar, windmills, batteries, etc. require more minerals (including REEs) to build than fossil fuel-based ones. A typical EV requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant. Since 2010 the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50% as the share of renewables in new investment has risen.

The Chinese Dominance

If we consider the availability of refined metals, China’s control is 35% for Nickel, 50-70% for Lithium and Cobalt and nearly 90% for REEs. Chinese companies have also made substantial investment in overseas assets in Australia, Chile, the DRC, and Indonesia which supply the minerals. Over the last 40 years USA, Japan, Australia stopped their own refining capacities due to environmental concerns and set up JVs in China or agreed to buy from China by supplying their concentrates. The world’s largest source today is Bayan Obo ore, found in Inner Mongolia. This is a highly lucrative deposit rich in REEs that has powered China’s rare earth elements’ dominance.

China values its dominance of REE market more for geopolitical reasons than commercial ones as a leverage to deal with trade conflicts and to address fierce power contests. As production reached an all-time high, China declared REE to be protected and imposed tight restrictions on exports. Currently, quotas are set up for domestic manufacturers. With this export reduction, the price of RE metals increased from an average of USD 9,461 in 2009 to USD 67,000 per ton in 2010. If China were to cut off exports, the results for the technology sector would be disastrous. This occurred temporarily in 2010 when China had tensions with Japan due to a maritime dispute. They stopped all exports to Japan.

Scenario Outside China

Considering the urgency, US International Trade Commission (USITC) prepared an executive briefing RRE supply chain in December 2020 for policy decisions. In 2019, China accounted for 78% of the total volume of US’ imports of REEs. Though many countries have capacity for extraction, only China has the capacity to refine to finished metals. Accordingly, the Department of Interior authorised to use the Defence Production Act to fund domestic mineral processing and production for critical minerals.

Australia released its Critical Minerals Strategy in 2019, the goal being to increase investment in the critical minerals sector, including downstream processing capabilities, and secure markets for Australian critical minerals products. While Australia is ranked sixth in the world for REE reserves of 4.1 million tons and third for production of 27,000 tons, many of these deposits remain untapped. Australia released a strategy to invest in extraction and refining of REEs and develop less energy and chemical-intensive processing methods to minimise environmental impact.

In November 2020, the first India-Australia Critical and Strategic Minerals Joint Working Group meeting agreed on actions to be delivered in specified areas of the signed MoU. This joint working group is a significant step in implementing the MoU on critical minerals between the countries. The group explored India’s need for critical minerals in the new energy economy and Australia’s strength in the sector. It also suggested ways for India-Australia partnership. The recent Resilient Supply Chain Initiative (RSCI) between Australia, India and Japan aims to develop dependable sources of supply and attract investment. Critical minerals could emerge as a key sector in the RSCI.

China has REE mineral reserves of 44 million tons and produces 1,40,000 tons per year. Russia has reserves of 12 million tons and production of 2,700 tons. It has announced plans to invest USD 1.5 billion on REE production to rival China. USA has 1.5 million tons known reserve and produces 38,000 tons. All the production is in oxide form and sent to China for refining. China produces 90% of the global demand for refined metals, most of it for their own use for finished application such as mobile phones, laptops, etc.

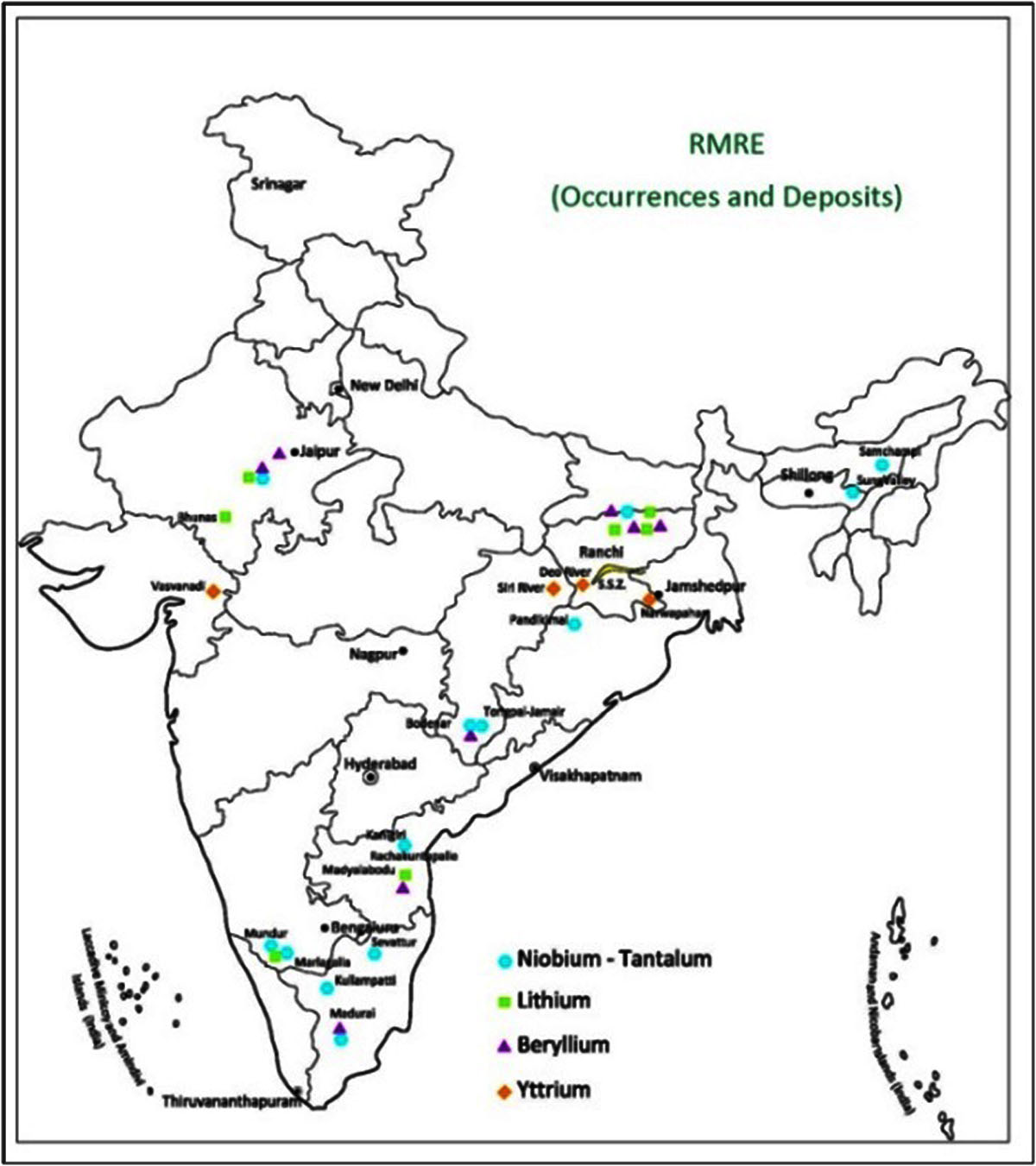

India Strategy on RRE

Indian Rare Earth Ltd. (IREL), part of the Department of Atomic Energy (AMD), Government of India, is the only Indian company extracting and processing REEs. According to AMD, as of January 2020 India had 12.47 million tons of Monazite (50-60% RRE oxide). Production in the form of REE chloride was only 4,215 tons in 2018-19. IREL has not set up further processing facilities for production of metals. Only AMD can extract Monazite as it contains radioactive metals and is exclusively used for defence. Major consumers of these minerals are actively seeking alternative sources, offering India an opportunity to enhance production. “India can very well be an alternative supplier of rare earth to the world as it has large reserves of Monazite and is unexplored for other rare earth minerals”, according to Jack Lifton, co-founder of the US-based Technology Metals Research. “What’s missing is a domestic downstream processing supply chain. If this is constructed, India will become a major producer,” he added.

India must seriously look at opportunities to increase capacity and production of upstream rare earths and set up downstream refining capacity with the help of the private sector. This field must be opened for private sector participation with adequate control on environment safeguards. JVs with US, Australia and Japan could bring in technology, finance and assured market. Presently India imports all finished components containing REE for applications in EV motors and batteries, windmills, mobile phones, consumer electronics, defence etc. Permanent magnet is the key component used in most of these applications and is made of rare earth metals. This will be huge opportunity for ‘Made in India’ value- added components for the above applications and for export.