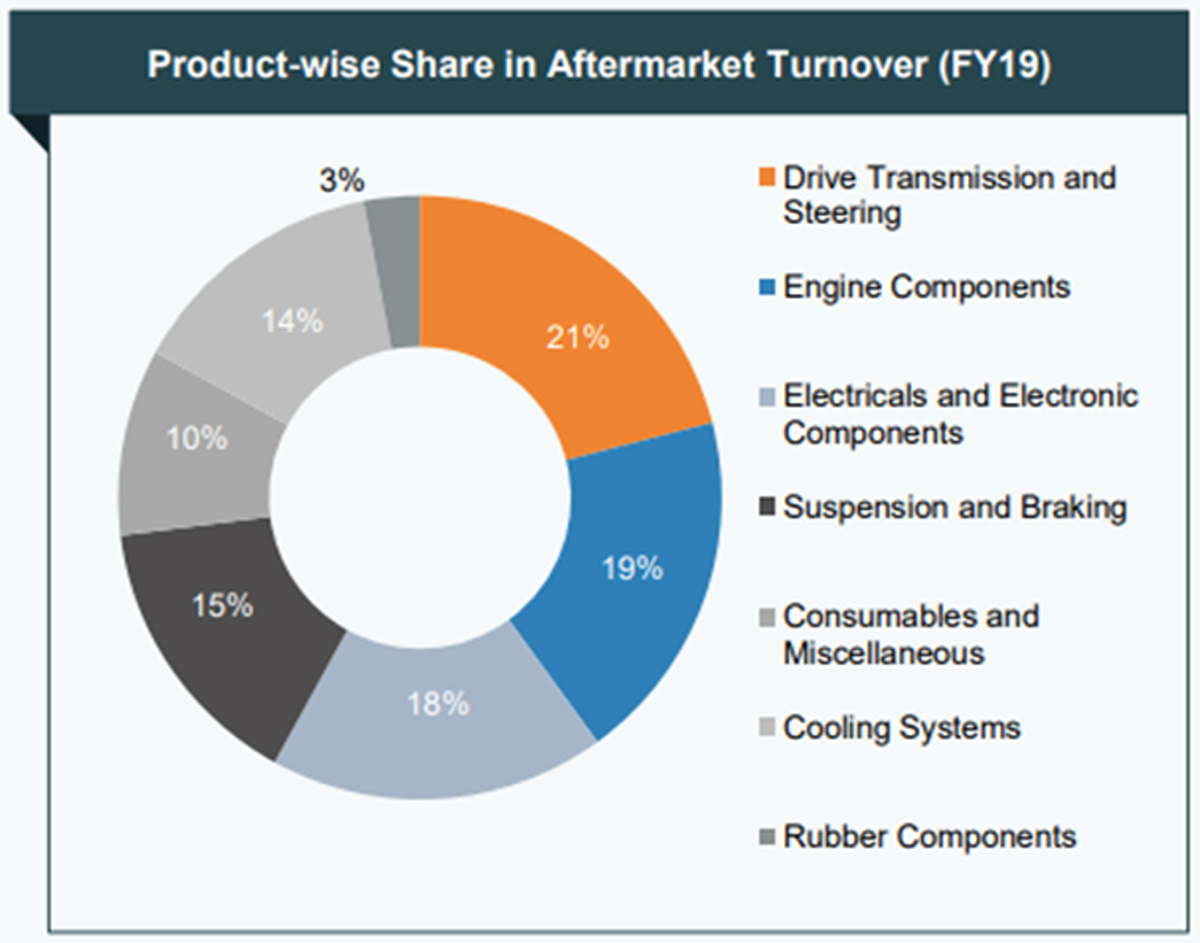

A look at the product-wise share in aftermarket turnover throws light on the four product groups, i.e., DTS, engine, electrical and electronic, and cooling systems taking lion’s share of more than 70%, implying that the component industries operating in the above product segment have a ‘pot of gold’ waiting for them to grab. But the question is whether the players in this industry are ready to grab this aftermarket potential presented to them? Visweswaran Sundararaman and Akshat Agrawal share some insights

While currently India is the sixth-largest automobile producer worldwide, after China, US, Japan, Germany and South Korea, thanks to robust demand and government policy support towards the ‘Make in India’ movement, it is expected to become the third-largest by 2026. The automotive components industry accounts for 2.3% of India’s GDP and 25% to its manufacturing GDP, providing employment to 5 million people, as per the Indian Brand Equity Foundation. So far the automotive components industry has registered a CAGR of 6%, reaching USD 49.3 billion in FY20 with exports growing at a CAGR of 7.6% to reach USD 14.5 billion in FY20.

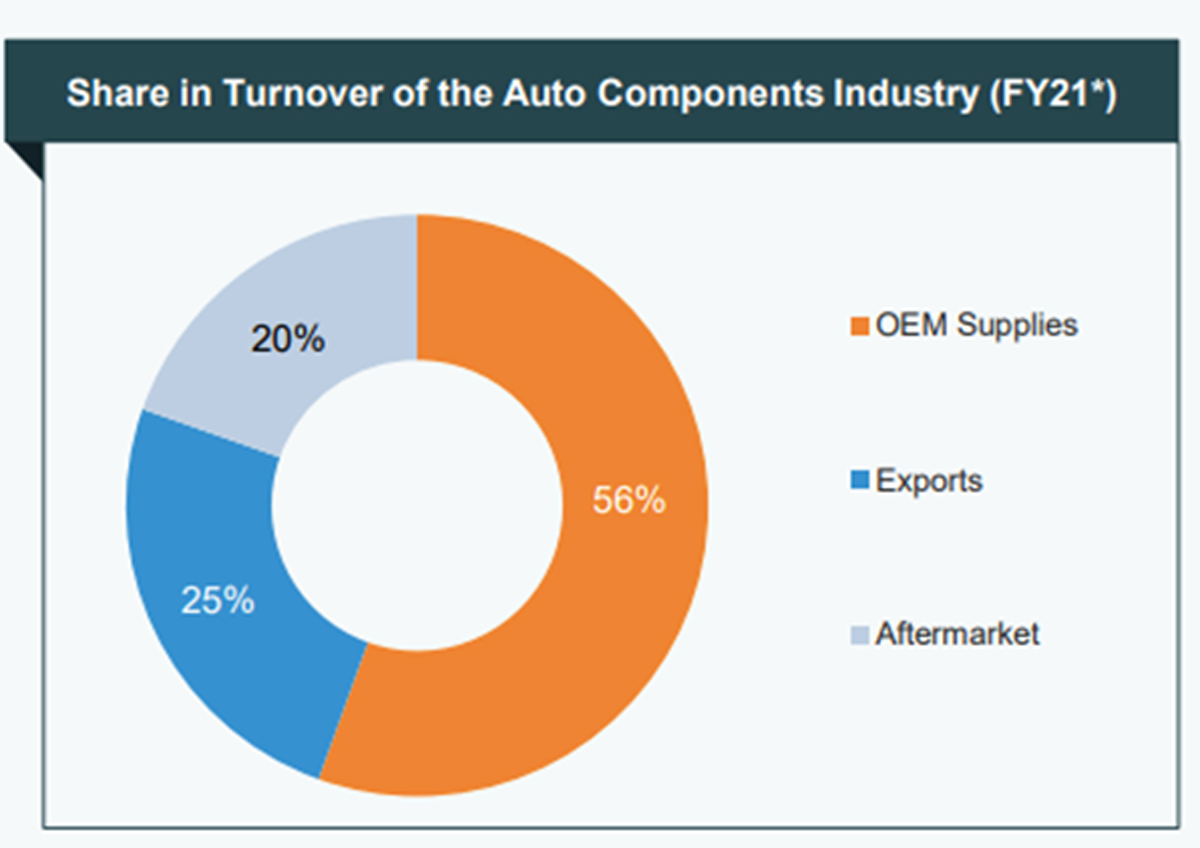

Catapulted by a manufacturing-friendly environment, the industry aims to achieve USD 200 billion in revenue by 2026 with exports reaching USD 80 billion. The automotive component supplies to OEMs contribute to 56% of the overall turnover with aftermarkets and exports sales contributing to 25% and 20%, respectively. The aftermarket turnover increased at a CAGR of 9.57% from USD 6.8 billion in FY16 to USD 9.8 billion in FY20 and is expected to reach USD 32 billion by 2026, as per data published by the Automotive Component Manufacturing Association.

Further, a quick look at the product-wise share in aftermarket turnover throws light on the four product groups, i.e., DTS, engine, electrical and electronic, and cooling systems taking lion’s share of more than 70%, implying that the component industries operating in the above product segment have a ‘pot of gold’ waiting for them to grab, as per the Automotive Component Manufacturing Association. But the question is whether the players in this industry are ready to grab this aftermarket potential or pot of gold presented to them?

Unique Industry Characteristics

While deep diving, one should be aware of the unique characteristics or insights with reference to this sector.

1) Long supply chain that includes Tier II vendor – Tier I vendor – OEM – distributor, dealer and wholesaler – retailer – mechanic – consumer.

• Except the consumer, everyone is chasing their respective monthly targets.

• Movement of stocks from one entity to the next entity is registered as ‘sales’ while the irony is that actual sale happens only when the consumer purchases from the outlet.

• Unlike FMCG, it is difficult to influence sale of automotive components as the significant portion of sale is driven by failure of parts that need replacement.

• Failure of parts can cause bigger damage, impacting vehicle utilisation.

• Hence, availability of parts at the retail outlets is not only very critical as consumers show close to zero tolerance time but also impacts future sales potential of OE with after-sales and service being important factors.

• It is not possible to predict all the possible failures and hence it is difficult to predict demand for automotive components in terms of what, where and when.

• The only way possible for the companies to react to such an unpredictable demand is through ‘forecasting’.

• There is a strong belief that forecasting enables them to ‘push the stocks’ closer to the point of sale.

• The co-existence of availability and unavailability across the network is not a strange phenomenon at all.

2) Same parts are available at one location while they can be unavailable at other locations.

3) In the same location, parts may be available at some point of time while unavailable at some other point of time.

• Factors such as stock ageing, territory intrusion or invasion, limited availability of working capital, space, etc., induce inconsistency in pricing behaviour at outlets.

• This market is the best example of a red ocean where the competition is fierce in terms of pricing and the consumer is confused about product quality.

It might be shocking to OEMs that the universe of competition is beyond their cognizance:

a) From OEM parts with ‘OEM’ branding and pricing.

b) From vendors who supply to OEM also competing with OEM in the aftermarkets.

c) Though the products are same inside the box, branding or packaging is different.

d) From the manufacturers who make similar products but do not supply to OEMs, i.e., known brands with comparable quality.

e) From the manufacturers who make cheaper products, i.e., unknown brands with compromised quality.

f) From the manufacturers who produce components and supplies with OEM packaging (spurious).

g) From the parts of dismantled pieces of older models in working condition.

4) While the spare parts demand is directly proportional to the age of the OE model (increased failure rates) whereas the age of the OE model is inversely proposal to spare parts reproduction due to availability of tools, jigs, fixtures, batch quantity, etc.

Key Challenges

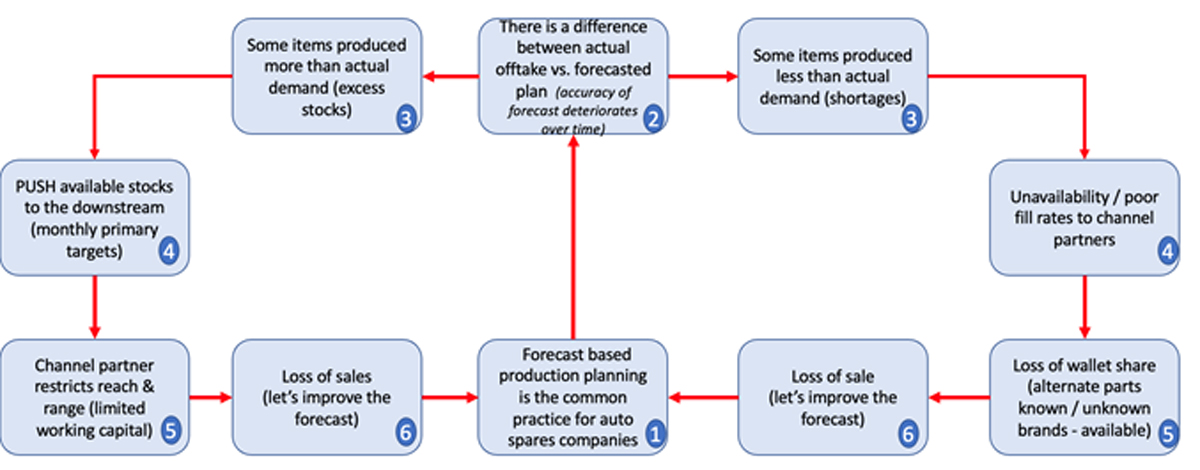

When forecasting is considered as the only possible way to deal the unpredictable demand and supply of the aftermarket, the forecasting signal mechanism upstream gets translated as monthly schedules for production to Tier I and Tier II vendors. However, actual production significantly varies from planned schedules thanks to various batching considerations or availability of resources such as men, machines and materials as well as change of schedules since the actual off-take could be different from the forecasted plan and change of priorities, i.e., OE versus spares versus VOR, etc.

This distortion leads to greater production of some items than the actual demand while some items are produced in lesser quantities than the actual demand. And this distortion grows wider and bigger as it goes towards the downstream thanks to multiplier effect due to the coexistence of two facts, namely, variation and dependent entities. Items produced more than the actual demand creates challenges including requirement of more space, more capital, capacity stealing, i.e., capacity used up in producing items which are not needed in the immediate horizon, material stealing, i.e., components used up in producing items which are not needed in the immediate horizon, etc. On the other side, when the production is lesser than the actual demand, it brings up a completely different set of challenges including parts unavailability, poor fill rates, order backlogs, etc.

While these challenges might continue, the reality is that managers must meet the monthly targets of both operational parameters (efficiency, inventory, fill rate, etc.) and business parameters (primary sales, working capital, collection, etc.). No wonder you observe a ‘sinusoidal behaviour pattern’ of this system, meaning that most of these metrics are ‘managed to be met’ in the second half of the month or the previous week or day in the form of production skew, dispatch skew, overtime or incentive payouts while the first half of the month is usually a low-key affair.

This distortion between forecasted demand versus actual market off-take is further amplified due to the above ‘sinusoidal system behaviour’ or forced behaviour thanks to monthly targets. The channel partners including dealers and retailers suffer the maximum brunt of this effect in the form of shortage of some items and surplus of some other items, perpetually. The limitation of the channel partner’s ability to influence the upstream and limitation of working capital forces him to take self-restrictive actions including number of retailers to serve, range of parts to keep, forced discounts (volume or age of stocks), promotion influencing sales, frequency of service to retailers, etc., leading to significant reduction in the brand owner’s market reach and range from their customers.

Reduction in reach and range has a direct negative impact on spares sales and hence puts pressure on brand owners to improvise the planning, meaning better forecast for upcoming period, implying going back to square one! This puts companies operating in the aftermarket spares, in a deadly spiral. When we go deeper with the Theory of Constraints (TOC), thinking of frameworks we understand what is holding (unresolved conflict) these automotive spares companies into the above spiral forever.

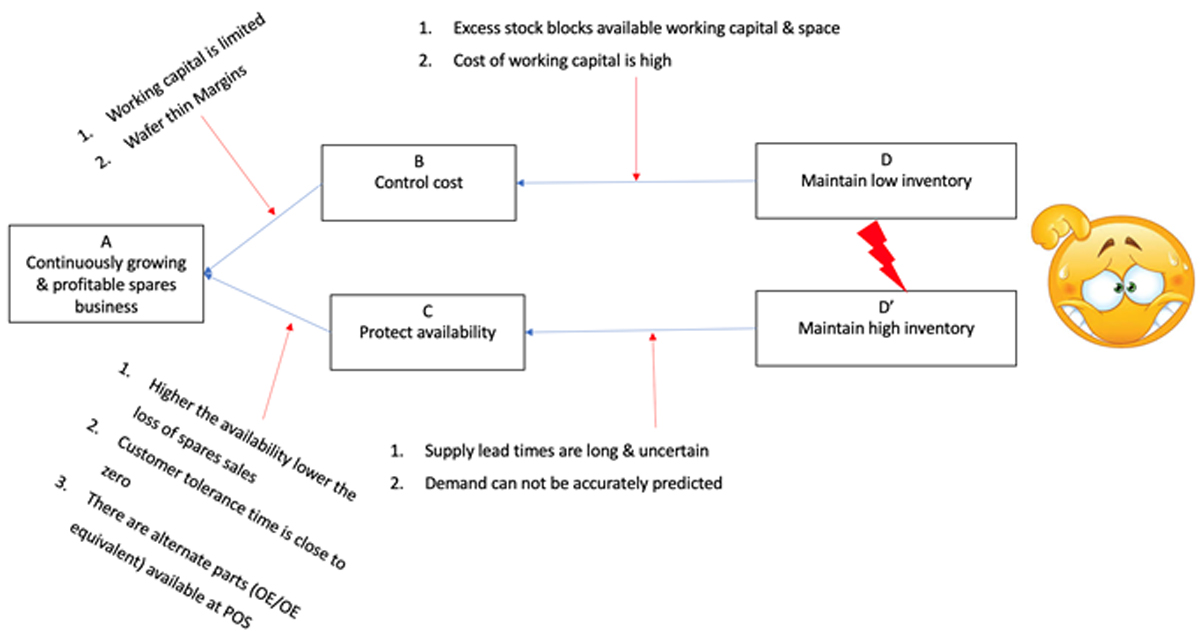

The Unresolved Conflict

The two necessary conditions to meet the common objective of most of these automotive spares companies are control cost and protect availability. But surprisingly, the actions to meet these respective conditions are in direct conflict with each other as described in the above logical diagram, referred to as conflict cloud – one of the logical tools of thinking process application, the Theory of Constraints. Conventionally, the conflict is taken for granted and hence the only way to meet both the necessary conditions is to assume that the demand can be predicted using a forecast. But when we challenge the long-held assumption that the demand can be predicted, oceans of opportunities open up in front of us.

Resolving the Conflicts

Here are some key points to ponder upon:

• Can the demand be predicted, especially failure-driven demands?

• Should we react to the unknown demand – pushing stocks to downstream?

• Should we respond to the unknown demand – pulling availability from downstream?

• Should we use forecast for both planning and also in execution?

• Does the forecasting error reduce with reduction in the forecasting horizon?

• Does the forecasting error reduce with the aggregation of stocking nodes?

• Should the upstream stocking node operate as transit point or holding point?

• Should we push for primary sales or should we enable secondary sales?

Inherent Potential

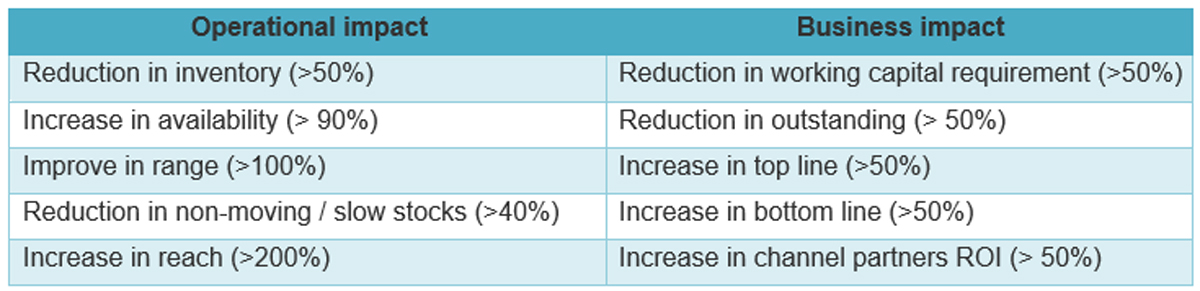

Companies who have successfully resolved the above conflict are advantageously placed to capture the inherent and upcoming potentials, both in operational and business parameters, including the below:

Visweswaran Sundararaman (visweswaran.sundararaman@goldrattgroup.com), and Akshat Agrawal (akshat.agrawal@goldrattgroup.com)