Old soldiers never die — they simply fade away, as the old song goes. That, precisely, is the sorry story of Indian logistics. Growing numbers of officers in the Indian Army are moving on to lucrative careers as managers in the industry, but none of them gives a fig for the fauji drivers in the non-commissioned ranks he’s served with.

It’s an observation Lt. Gen. Vishnu Kant Chaturvedi corroborates. A retired officer takes a “good while” to find his feet in the world of private corporations, but when he does it’s all about his own personal advancement from then on, the gunner-for-life from the 99 Forward Regiment (Sylhet) concedes.

That the vast reserve of veterans from the finest fighting force in the world should go untapped while their ex-superiors devote all their energies to climbing the corporate ladder is a tragedy of national proportions. The indifference to ESMs certainly isn’t the fault of fleetowners alone. Gagan Chaturvedi says he’s encountered it on more than one occasion, and it makes him marvel.

In 2017, as managing director of G-Trans Logistics (India), he faced an inexplicable resistance from a former Army major, operations manager at an e-commerce giant, to the deployment of a fleet of 100 light trucks he’d just bought to service the bulk of that company’s express delivery requirements in the NCR, that he planned to man with teams of fauji drivers.

Instead of the 100 agreed on, the contract he was given was for 30 trucks only. The perfidious ex-major quit in short order and set up his own transport business to corner the balance. Not only did he not employ a single fauji himself; he left Gagan no choice but to cap his own fauji driver hires at 25 — and to seek the patronage of a leading e-comm competitor to keep those expensive CNG trucks running.

To make matters worse, the civilians who made up the bulk of his driver pool, all from trucktown Mewat, perversely went AWOL en masse the entire month of Ramadan in May and June – with the vehicles, – bankrupting the ₹45 crore business, which had grown at 300 percent year-over-year till that point.

It was an epiphanic experience, and sowed the seeds of what would, two years later, become Signodrive Logistics Pvt Ltd (Signo).

Only months earlier, Gagan’s fleet manager had introduced him to another ex-major, a people person after his own heart who headed placements for Maxplus Logistics. G-Trans needed drivers for the prospective e-comm contract and Sulekha Sharma was scouting around for new business. They agreed to a trial, and Gagan’s first close encounter with the ESMs left a deep impression.

It took him till April 2019 to emerge from insolvency and rescale the business to a “limited operation” with Flipkart, but all that time he had his eye out for what he could do next, for a plan that wouldn’t need “much capital” to put into effect. He’d been observing Maxplus’s faujis at work for SpiceJet, and the more he watched, the more he was convinced that there in front of him was THE answer to the “pain points” of the (now) ₹1.5 lakh crore logistics industry.

Several conversations with advisor, friend, and confidant Shailesh Kaul later, the Signo concept had begun to crystallise. Shailesh, now chief commercial officer at the startup, says Gagan was in awe of the ESMs, floored by their dramatically different “attitude and professionalism”, the savings on fuel and maintenance that accrued from the vehicles they drove for him, and the complete stoppage of pilferage during the three months they were in his employ.

Men and the art of missile-launcher maintenance

According to Lt. Gen. Chaturvedi, who retired in 2011 as Director-General Manpower Planning & Personnel Services, as many as 5,000 of the 70,000-odd men that retire from all three services each year are drivers.

Because they’ve been posted to all parts of the country – each moves at least four times in his career, often five, alternating between peace and field locations, – fauji drivers aren’t topographically challenged. Open roads, steep mountain trails, crowded city streets — an ESM is equally at home on all.

For your friendly neighbourhood fauji, defensive driving isn’t a skill; it’s second nature. Problems with brake wear and clutch life? The fauji’s your man, far better-trained and practised in the science and art of vehicle maintenance as he is, than the best-trained civilian driver (can be).

Pre-departure checks? A fauji won’t turn the key in the ignition without them. Secure your load? Consider it done. Rotate tyre positions? Save the time and expense of a visit to the service centre — he’ll do it himself. Breakdown maintenance? Should it even come to that, he’s more than up to the task.

Unlike his typically untrained civilian counterparts, a fauji is extremely resourceful when it comes to emergency repairs and keeping his vehicle going in tough conditions. “An ESM can be depended on to guard his vehicle with his life,” says Maj. Sulekha, who joined Signo as chief sourcing officer (effectively, CHRO) in March.

Paraphrasing English military historian John Keegan, she points out that a fauji, when committed to a task, cannot compromise; his is an unrelenting devotion to the standards of duty and courage … and to “not letting the task go until it’s been done”. All in all, a bulletproof kernel to build a sustainable outsourced fleet management enterprise around, considering that “90 percent of a fleetowner’s job is managing drivers”.

At its core, Signo is a social enterprise conceived to connect faujis to fleets at planetary scale, leveraging the latest advances in artificial intelligence to make the most beneficial matchups according to the particularised needs and preferences of both sides. “We take great pride in the opportunities we give our drivers and the close attention we give our clients,” the CEO proclaims on its website.

Like no other logtech startup in the land, Signo’s team actually possesses hardcore supply- and distribution chain expertise, covering the entire breadth of logistics functions to depths of both know-how and know-why that are unequalled in the industry — a reflection of more than 150 years of executive experience combined.

Of FASTags and faujis

The company has deployed more than 300 faujis since January to fleets signing on for its driver-as-a-service, including such big names as DHL SmarTrucking (50+) S.M. Auto Group (45), Harsh Logistics (40), AVG Logistics (25), and BLR Logistiks (25). The number, Gagan reckons, could have been as high as 1,000 were it not for the disruptions due to the state governments’ overblown COVID response.

The minimum commitment Signo asks is for a year, though it’s offering contracts of a maximum of three years only at the moment. The fleetowner must provide up to 25 items of information upfront, such as the age, composition, and fuel consumption of individual vehicles in, his fleet; the route(s) and route expenses including tolls and payoffs to RTOs and at border checkposts; and what his problem areas are (driver retention/fuel theft/unionisation, etc). Signo tailors its proposal accordingly.

Every client is guaranteed a driver and transit-time performance, plus a minimum 5 percent fuel-efficiency gain, going up to 15 and potentially even 20 percent, according to the service level agreed in the contract. Signo bills him every month for the equivalent of the driver’s salary plus a management fee proportional to the SLA.

At the most basic level, route expenses and tracking are the client’s responsibility. Level 2 entails Signo additionally shouldering the responsibility for delivering the client’s vehicle from A to B, including paying all route expenses at actuals, while Level 3 layers on maintenance, tyre performance (in partnership with Fleeca.in), and consumables.

Not every fleet operator can expect a driver from Signo — only those that treat its faujis with the deference they are due. The company is very particular that, among other things, they are provided suitable rest and clean sanitation facilities onsite; that their feedback regarding the state of repair of the vehicles assigned to them is appreciated and actioned; and that their hours-of-work protections under the law are strictly honoured.

In the interests of the safety of drivers and cargo, a truck that’s required to cover more than 400 km in one work day will necessarily be manned by a team of two – this is non-negotiable – and the client billed accordingly. Signo monitors its drivers’ duty performance individually and in real time by means of a smartphone app with a SIM tracking function, and provides the client with daily MIS reports.

The company was an early tenderer for a requirement by the state road transport undertaking of Uttar Pradesh for 1,000 drivers, but Gagan says there’s been no movement on that contract because … COVID. More recently, Signo’s snagged a contract with Bisleri for 1,000-odd drivers to operate the packaged drinking water giant’s entire fleet of Tata 407/709 delivery trucks pan-India. It placed the first five of an initial commitment of 17 drivers with Bisleri’s operations in Chennai last month.

For long hauls, it has begun to offer a premium-priced pay-per-kilometre plan as a flexible alternative to fixed-term contracts. On 1 September Parkkot Maritima Agencies, a Goa-based operator of 120 trucks that typically cover up to 10,000 km a month apiece, replaced 50 of its existing drivers with ESMs, whom it will pay the standard salary plus an incentive for every kilometre driven over and above a 7,500 km floor commitment.

At the next level is its end-to-end fleet management proposition for “key accounts” that covers the full spectrum of their truck-in-transit needs – driver, tyres, on-demand fuelling en route by means of smart bowsers, tolls and highway expenses, insurance, maintenance, you name it – or any subset thereof for a single all-in price per km.

For pioneer client Inland World Logistics, Signo has assumed pretty much complete operational control on the Delhi–Mumbai and Delhi–Kolkata lanes, for a per-km charge that factors in the drivers’ salaries, diesel, and route expenses.

As its fleet management relationships mature, Signo expects eventually to be entrusted with the authority to specify and configure client vehicles and equipment, sensors, and telematics devices; to independently monitor and process their outputs; and to derive strategic insights from vehicle and driver data that it can leverage to maximise fleet performance.

Co-founder and chief business officer Jitesh Pandey sees solid prospects for services such as the above with rapidly expanding new-generation fleets DHL Supply Chain/SmarTrucking, Delhivery, et al, but says the biggest potential beneficiaries of Signo’s most powerful value proposition will be the three-million-odd owner-drivers and small fleets of up to 10 trucks.

Managing a multiplicity of operating expenses is a “huge struggle” for most every player in this segment, which accounts for an estimated 60 percent of the total fleet pool. A new PAYG (prepaid) offer from Signo gives them access to all the same fleet management services as the large fleets, the upfront pricing varying inversely in proportion to their kilometrage commitment.

Another powerful service it soft-launched in June, that it doesn’t want reported in more detail yet, could potentially do away with the 1.5 lakh brokers and other rent-seekers that hold sway over the sector once for all, and tear down the structural inefficiencies they’ve built into the system that the existing freight matching startups have left largely untouched.

The ultimate ambition is to evolve into a driver-on-demand platform à la Uber, which will enable Signo to better satisfy the diversity of route and working-hours preferences of its driver pool. That, however, is going to require a minimum of 1,000 “active backup” drivers on its rolls at each demand location to guarantee supply, according to chief technology officer Mukesh Deogune, a 2020 graduate from IIT-BHU.

Provided the right types of trucks are available on lanes for which the relevant demand is, Jitesh believes fleetowner acceptance of “driver by the hour” will finally fuel the growth of relay trucking — the single assetholder model having signally failed. The task, he explains, is to match both, truck type to load type and driver to truck per route segment, to be able to deliver the best value.

All aboard!

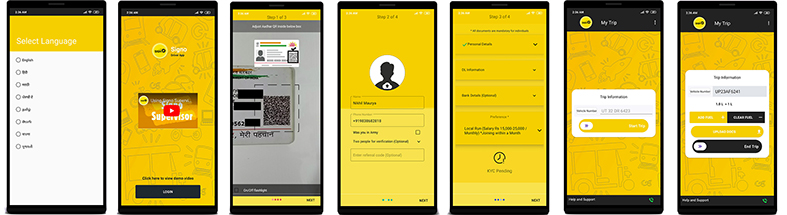

The company has a completely automated registration and screening process, which sorts drivers according to their preferences and whether – and how well – they meet the functional requirements.

A conversational AI bot, presently available in eight vernacular languages, elicits essential details of a registrant’s location, specific vehicle skills, and length of experience. Within 45 seconds he receives by text message a shortlist of open jobs available within a reporting radius of 100 km.

Clicking on any one of them as an expression of interest connects him via the bot to a “supervisor” (a JCO) for that region, who informs him personally of the specifics of the job description and asks him how soon he can join. The close of that conversation triggers another message with details of the date and time he has to report at and the address he has to report to, plus the name and number of the supervisor.

It also initiates the second level of engagement, in which he has to upload proofs of identity and credentials (driver’s licence, Army number, PAN, and Aadhaar if available) via – and take a selfie image from within – the Signo driver app.

The system runs cutting-edge optical character recognition (OCR) and facial matchmaking algorithms developed by Mukesh and his geek squad to verify the authenticity of the documents submitted, and accepts the driver’s profile as genuine only if the result is a positive match with a high degree of probability. At the same time, it also returns criminal background checks via APIs to the relevant government databases.

The whole process takes less than five minutes.

The driver reports to the supervisor at the job location on the date and at the time appointed, and is signed into the system via the supervisor’s app, which records the start of his employment and pushes a welcome message to his own app with details of his job, salary, etc. On entry of his bank information his salary is credited into his account.

Technology may help filter Signo’s 10,000-strong driver pool for functional fit, but ensuring that its faujis fit behaviourally into a shared emerging corporate culture very different from the one they’ve been used to for up to 20 years of their lives, is going to take robust (physical) recruitment procedures.

Assisted by senior leadership development consultant Anand Chaturvedi, the company is working on a streamlined onboarding process that will help it maintain coherence of purpose during its present rapid scale-up. Together, they’re also thinking through policies to manage an ESM’s entire lifecycle within the company with a view to delivering an exceptionally rewarding career experience.

Chaturvedi, who retired from confectionery megacorp Mars last year after 10 years as leadership facilitator for APAC, the Middle East, and South Africa, believes Signo has what it takes to exemplify the Economics of Mutuality in action. EoM is a groundbreaking business reengineering methodology developed within $37 billion family-owned Mars, Inc, that seeks to focus enterprises on the service of society and the environment (away from their obsession with shareholder primacy) for sustainable growth and profitability amid the emergent challenges of the 21st century.

If Signo’s value-sell jells, not only will old soldiers never die; they simply won’t fade away.

A pedigree nonpareil

Co-founder and director Piyush Chaturvedi, the éminence grise of the Signo team, got into the industry by accident 30 years ago. He’d started out in textile sales 4½ years prior, but decided at a venture to try his hand at marketing — with, as it happened, Transport Corporation of India (TCI).

Though he hadn’t planned to stick around, he soon found himself in his element, eagerly accepting growing levels of operational responsibility. Promoted to divisional manager in Mumbai by 1994, he was among the first TCI executives to become part of Gati when the door-to-door business was carved out of India’s largest transporter the following year.

At the turn of the millennium, as general manager for region north, Gati’s largest, stretching from western UP to Srinagar, a declined transfer occasioned his exit — and return to Mumbai.

There, Piyush (as he insists he be called) went on to establish himself as a pillar of Reliance India’s emergent logistics division and architect of its Relogistics joint-venture model that grew Reliance Logistics (RLPL) into India’s second-largest integrated logistics business in five years flat.

Additionally, as director of five of the 16 majority owned Relogistics JVs across India, he personally negotiated profitable backhauls for the trucks they operated, from the Surat, Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Vidarbha, and MP regions towards the Reliance locations in Patalganga, Nagothane, Silvassa, Hazira, and Jamnagar.

Another of his responsibilities was to set up, in 2003–4, the distribution of diesel and petrol from the Jamnagar refinery to 1,430-odd fuel stations operated by Reliance Petro Marketing (now Reliance BP Mobility). The Relogistics fleet at the time consisted of 750 JV-owned trucks, 550 dedicated trucks, and more than 2,000 open-market vehicles, to which 3,000 “attached” tankers were added.

To help ensure security in transit, RLPL developed its own telematics service on the Reliance Infocomm CDMA wireless network that delivered vehicle location and load status alerts via SMS. Subsequently branded Trans-Track and marketed to external customers as part of Reliance Petro’s Trans-Connect portfolio of fleet services, it sparked off a number of pioneering innovations in the industry.

Another vital element of the Relogistics model thenceforward was the mandated use of Reliance Trans-Connect fuel cards by the 16 “IBUs” (individual business units). “Considering that fuel made up 45 percent of the driver’s route expenses, and that he traditionally used to be handed up to 70 percent of the cost of the freight in cash before the trip, we were able to reduce the volume of cash in the system dramatically, with a knock-on effect on efficiency,” he says.

Reliance earned by selling diesel to this captive market, from the vehicle tracking service, and from its share of the revenue from the transport.

Relogistics went multimodal in 2005–6, and added package delivery in 2006–7. That year the IBUs were merged into Relogistics India (RIPL), a 100% subsidiary of RLPL. By now, there was a clear emphasis on the petroleum logistics segment — Reliance commanded a 14.3 percent share of the market for diesel and 7.2 percent for petrol, even though its fuel retail presence consisted of fewer than 3 percent of the total number of outlets.

Busy in the background, Piyush started a separate division dedicated to building up the supply chain for Reliance Retail, complete with warehousing and retail transport management capabilities for the fast-growing chain of Reliance Fresh stores.

In 2007, sales at the fuel stations dropped precipitously owing to the substantial selling price differential to the subsidised public sector competition, and by mid-March 2008 all 1,432 were closed down. The Relogistics business model collapsed, but Piyush had already moved on to his next assignment, to set up an asset-based logistics business for Gammon India — from scratch.

As vice-president overseeing a ₹300 crore budget, he was tasked with creating an end-to-end cold chain onshore for imported cargoes. Market research took a year, but then the financial crisis hit and “big US and German companies” he’d been trying to persuade to invest withdrew and the business never took off.

What did, though, was an air express cargo foray as the general sales agency for GoAir. Piyush was joined by his sister’s son Jitesh, who’d followed him from RLPL, where his role as western region product head brought an 11-year career in LTL and express cargo to a head. The two worked closely with the smallest of India’s major private airlines to monetise the spare belly capacity in its Airbus aircraft, helping it to realise a far superior value contribution to its revenues than its “budget” passenger fares.

At the beginning of 2010 he threw in his lot with Reliance Infrastructure (RInfra), accepting the entire logistics responsibility for the 6×660 MW Sasan Ultra Mega Power Project, for which RInfra was the EPC contractor. Working on a budget of ₹300 crore over the three years of the project, he had to plan and execute movements of boiler and turbine generator islands weighing up to 360 tonnes each from Chinese supplier Shanghai Electric Company, imported via the Kolkata port.

Piyush’s next assignment was to help set up RInfra’s cement plants in Maihar near Satna (MP), Kundanganj near Raebareli (UP), and Butibori near Nagpur (MH), including not only the project logistics but also the movement of clinker from the composite plant in MP to the other two grinding units, and of gypsum and flyash (from Reliance Power units) to all three, besides the distribution of the compounded cement to all corners of the country. All this involved coordinating the movements of a market fleet of 300 vehicles per day, and “lots of movements by rail”.

Elevated in 2014 to senior vice-president in charge of logistics with the added responsibility of corporate procurement for the entire Reliance Group, his remit now included administrative procurement – of manpower, security, and facilities management, – oversight of the group companies’ guesthouses, and the appointment of consultants.

Following RInfra’s sale of its Mumbai electricity distribution business to Adani Electricity, he moved over in August 2018 and held charge of project movements of transformers, receiving stations, and cables till he superannuated last June.

At Signo, he’s bringing the weight of three decades of experience in – and unrivalled understanding of the intricacies of – trucking, project execution, and man-management, plus his wealth of connections in the industry at the highest levels, to bear in the startup’s rapid rise despite COVID-19 and the ever-shifting patchwork of lockdowns the country has seen over the last five months.

Been there, done that, and back

Starting out in the industry at Relogistics (Delhi) in 2004, Gagan Chaturvedi built a successful career in business development via stints at three other organisations. But his heart’s desire always was to start an enterprise of his own.

His first stab at entrepreneurship at age 30 in 2010 may have lasted only a year and a half, but it demonstrated his willingness to take big risks. First off, as the sole subcontractor to Agility Logistics, he undertook the mammoth responsibility of arranging the placement and removal of all the equipment for the XIX Commonwealth Games, orchestrating the movements of 250 vehicles of a variety of types, ranging from golf carts to heavy cranes, that he’d hired from a handful of vendors.

At the conclusion of that project he turned his attention to the construction of the Yamuna Expressway, securing a “30 percent” share of the cement movements from Jaypee Cement’s grinding unit in Roorkee to concrete batching plants onsite. Encouraged by earnings of ₹5,000 per trip from each of the 100 open-market semitrailers he ran, Gagan decided to buy two “22ft. 10-wheel” trucks of his own besides.

What he hadn’t reckoned with were the “heavy” maintenance expenses that would attend the operation of those trucks in overload, or the extortionate RTO challaning he’d be subject to at the behest, he believes, of a larger competitor, but he was quick-witted enough to exit the business when he did, ₹15 lakh in the clear.

In parallel, he picked up his smarts in 3PL, setting up and running a regional operation for the Easyday grocery-store chain that was in the process of being set up by Bharti Walmart. It consisted of three leased warehouses in Delhi, Ghaziabad, and Lucknow, and 45 aggregated vehicles that delivered stocks from the mother warehouse in Alwar to 11 locations spread across from Jaipur to the NCR, Lucknow, and Bareilly.

After nine months, when a request for a price revision was denied, Gagan decided it was high time he moved on and gained more experience at an established transport enterprise. Two and a half years, and a couple of stints as head of northern-region ops for two traditional logistics companies later, he was ready for a new adventure…

…when an invitation by a friend to do business with Hyundai subsidiary Mobis India Ltd kick-started his entrepreneurial ambitions once again. Within three months he had his vendor code in hand, had deployed six 32ft. container trucks for the aftermarket arm of India’s second-largest carmaker, and was earning ₹5 lakh a month. “Not satisfied”, he wanted to do more.

That *more* was to revive G-Trans as a private limited company (he’d run his earlier business as a sole proprietorship under the same name), with both FTL and LTL operations, plus warehousing and transfer of spares for India Yamaha Motor from its plant in Noida to Sriperumbudur near Chennai using seven 32ft. trucks.

By 2017 G-Trans had grown to a fleet of 1,800 leased vehicles, and was a “top five” vendor in the NCR to India’s largest retailer and the biggest names in e-commerce. A chance conversation at a conference with the country head of one of those e-comm giants introduced him to the prospect of a big add-on contract, but negotiations were sabotaged from within and, as described in the opening paragraphs of this article, Gagan soon came to grief.

However, it was this very experience that proved to be the genesis of Signodrive Logistics, arguably the biggest idea in the industry in a long, long time.

Shero for the long haul

Sulekharinki Sharma, the daughter of a Service Corps (ASC) officer, joined the Army with a master’s degree in biotechnology. Following her dad’s advice, she opted for the Ordnance Corps (AOC) after her basic training, and was assigned to 1FOD (1 Field Ordnance Depot), going on to ace her foundational degree at the College of Materials Management in Jabalpur.

Her first assignment was to the ammunition depot in Ambala, followed by two extra-regimental postings in succession as officer in charge of technical stores at workshop units of the Corps of Electronics and Mechanical Engineers in Suratgarh (Rajasthan) and Kalimpong (West Bengal). At both, she had oversight of the inventory of spare parts for “everything from a motorcycle to a tank”.

In her seventh year, she chose to move back to the headquarters of her parent unit in Udhampur (J&K) and was put in charge of a depot “four times larger” and an inventory in excess of 22,000 items. As depot commander for three years, she mastered the unbelievably intense advance winter stocking effort in the three summer months that keeps the front line in Leh and Ladakh fighting fit for the whole rest of the year.

Flawless coordination was vital – “getting the stores ready for the ASC battalions to pick up, arranging for escorts, intimating the receiving units, and arranging a plethora of permits and passes”, among other exigencies, – but Sulekha, now a major, managed the show with élan.

In parallel, she was given additional charge of procurement and provisioning, putting a ₹200 crore budget at her disposal. This necessitated a deep dive into demand patterns so that purchasing priorities could be attuned to the immediate needs of the individual units for more rapid replenishment.

Streamlining the entire resupply chain required Maj. Sulekha to collaborate with both, local suppliers and central procurement agencies, and liaise with the other central ordnance depots besides.

Discharged with distinction in 2016, her decade of experience working with men and materials, and enviable network of contacts, made her a shoo-in for the role of chief operating officer at Maxplus Logistics, which had just entered the manpower logistics business and was looking to grow beyond its anchor client SpiceJet.

There, for the first time in the country, she initiated experiments with fauji drivers on long hauls, with encouraging results but lots of sobering learnings as well. One of those, no doubt, was that Indian fleetowners, all their bleating about the “driver shortage” notwithstanding, are quite comfortable with the situation as it is and extremely resistant to adjusting the way they think and operate to accommodate the idiosyncrasies and scruples of an ESM.

But there’s a difference now. As chief sourcing officer at Signo since March this year, she’s better placed than ever to get that powerful vision of the fauji driver to finally take flight.